The Doer and the Payer: A Simple Approach to Scale

Growth and scale aren't the same thing. Here's what you need to know if you're serious about getting to scale.

This article was originally published by Stanford Social Innovation Review on August 21st, 2016 with the headline - The Doer and the Payer: A Simple Approach to Scale

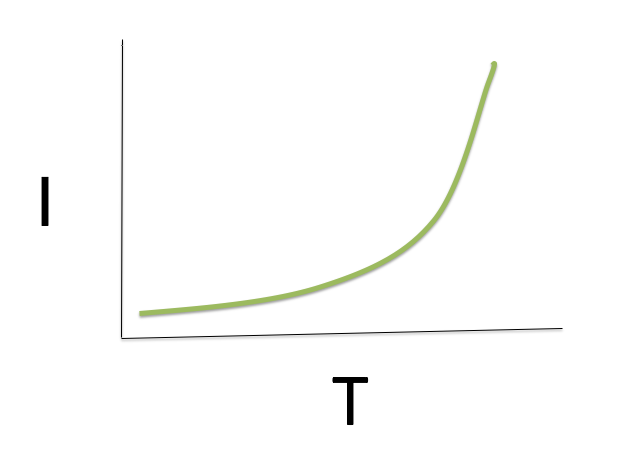

At Mulago, we obsess on the notion of social impact that goes to scale. Since we’re usually willing to pay for lunch, people often come to talk about “going to scale” and “scaling up our work.” Most of the time, the word “growth” would better capture what they have in mind. Growth is a fine thing, but scale is what solves problems, and so scale is what we look for. When we talk about “going to scale,” this is what we mean:

Call it exponential, geometric, what have you—the point is that the curve steepens, and impact (I) accelerates dramatically over time (T). We know it takes a while; we know that “the hockey stick” is bullshit, but in the end we need to see something that looks like that curve.

Since we need to talk about scale—and design for it—with lots of organizations doing lots of different things, we wanted to find a simpler, more usable way to talk and think about it. Over time, we realized that if you want to get to real scale, two questions really matter: 1) Who’s the doer, and 2) who’s the payer?

You’ve got a proven model at big scale—the thing you do. Who’s going to replicate—do—it, and who is going to fund that replication?

Thinking about the doer is simplified by the fact that there are only four choices:

- You: running an NGO or business that gets impact to scale through growth or leverage

- Lots of NGOs: replicating your model

- Lots of businesses: replicating your model

- Governments: delivering your model through programs and policies

That’s all you get. Pick the doer that will dominate at a scale of a million and beyond. They’ve all got pluses and minuses, like this:

- You: Having full control over replication means that you can deliver a complex model at high quality. Building and growing a really big organization is a pain in the ass, especially in a dysfunctional funding market.

- Lots of NGOs: Plenty of bandwidth there, and it shifts fundraising off your back, but NGO’s are notoriously bad at implementing other NGO’s ideas; either they don’t want to, because they perceive a need to seem unique in the aforementioned dysfunctional market, or they try to implement on the cheap and fail to get the same impact.

- Lots of businesses: We’re not interested in one-off businesses—it’s industries that solve problems. Obviously, to make use of this doer, a solution needs to come with a profitable business—the more profitable, the more imitators—and that precludes a lot of important solutions. Capital remains a problem: Mainstream investors won’t touch most of this stuff, and impact investors are way more risk-averse than the name implies.

- Governments: They have big bandwidth, lots of resources, and a mandate to serve—and they’re probably the only way a lot of basic service solutions will scale. They are often inefficient, inconsistent, and corrupt. Have fun.

That’s it. Pick one, and pick it early: A model will only scale if it is designed with the doer in mind. Governments don’t do complicated (nor, in most cases, do other NGOs). For-profits too often leave out the very poor. NGOs that grow really big usually can’t maintain disciplined replication of one solution, because they have to meet a burgeoning payroll (see dysfunctional funding market).

Got one? OK, now pick a payer at scale. Conveniently, there are only four them as well:

- Customers: revenue from product sales

- Taxes: revenue raised by governments

- Big Aid: multi- or bilateral revenue from rich governments to poor governments; sometimes delivered straight to the doer, sometimes delivered via government

- Private philanthropy: from Gates to the individual small donor

Investment gets a business growing, but eventually you need to sell a lot of stuff to a lot of people. Most poor governments don’t collect much in the way of taxes. Big Aid is big, but the paperwork and restrictions are a huge drag. Private philanthropy is a mess, but once you get some momentum, it gets easier—up to a point.

Once you’ve picked your doer and payer, you’ve got the context you need to think usefully about the scalability of your model. Three questions:

- Is it cheap enough? This is about cost-effectiveness—the cost-per-unit impact—but it’s also about the price the payer is willing to pay. If you want to scale up your innovative community health worker model, what’s the health ministry’s price point for per-capita coverage? If you have a product to sell, will customers pay enough to give you (and your imitators) a decent margin?

- Is it simple enough? If your model is complex and requires ninja-level execution, then you’re going to be doing it yourself. Governments are pretty hopeless at disciplined execution, and NGOs are often not much better. Even businesses won’t be able to replicate a model that is very complicated.

- Is it adaptable enough? Cookie-cutter solutions don’t work very often. The best models use a systematic process to generate locally appropriate solutions. If your model is rigid, or if it depends on limited set of circumstances or a rare kind of talent, then it’s probably going to hit a ceiling pretty quickly.

So if you’ve picked your doer and payer at a million beneficiaries (and sometimes there can be more than one of each, but it is usually better to design around one), and think you’ve got something scalable, try this: Pick the next order of magnitude from where you are now, lay out your doer(s) and payer(s) for that, then do the same for the next order of magnitude. If you’ve laid it out for a million, go to 10 million – hell, go to 100 million. What emerges from that is the outline of a strategy to get to scale—and the chance to assess whether you’ve got a solution that can make the trip.

Everything must be iterative; your doer and payer may change over time, and your model will certainly evolve in response to the reality bath that is the real world. It won’t be easy, but it can be a lot of fun, and this simple framework can help you make sense of the changes and maybe even get ahead of the curve.

Go forth and scale.

Impact in your inbox

The best stuff we run into, straight to your inbox. Zero spam, promise. To see past issues, click here.

.png)

.webp)